In James Cameron’s 1984 sci-fi blockbuster, The Terminator, a cybernetic assassin travels back in time to terminate a woman, Sarah Connor, whose unborn son, John, will one day lead a successful rebellion against the machines.

With a budget of $6.4M and iconic lines like “I’ll be back,” Arnold slayed his way from the big screen into our hearts, spawning a $3 billion movie franchise and arguably altering the face of California politics forever.

Although we haven’t unlocked time travel, SlipSeat’s strategy for eliminating the driver shortage is similar. We’re going after the thing that is giving it life. If we’re successful, the shortage will just go away. It will be as if it never existed.

Using macroeconomics to understand the US truck driver shortage

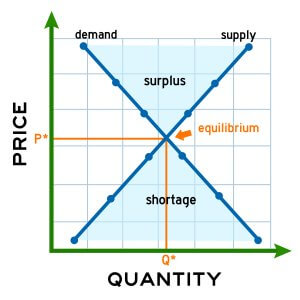

In the world of macroeconomics, labor markets behave like living breathing entities and shortages are tools that markets can use to get what they want. Markets only want one thing. They want to be in a state of equilibrium or homeostasis where the market is in balance. In labor markets, this is also called full employment, which is when 95% of a workforce is employed.

In equilibrium, everything just kind of clicks. People still leave jobs but it’s not hard, expensive, or lengthy to find a replacement worker or company, depending on the need. Economically speaking, when things are in balance, everything runs efficiently.

In trucking’s case, the truck driver labor market is out of balance because a very large portion of current and historical Interstate driver/carrier transactions are/have been macroeconomically corrupt.

Corrupt transactions do not account for all the risk and cost that drivers experience. Individually, drivers don’t know if their transactions are at fair market value, many times until months after the transaction occurs. In many cases, this causes job disillusionment, which can lower morale and increase absenteeism and turnover, among other things.

In aggregate, corrupt transactions represent bad data points which skew expectations for others, creating confusion and ambiguity for Interstate drivers as a whole. Because very, very few of them are operating at fair market value, the driver collective has no idea what the true market rate is for their services. Mass confusion and ambiguity in turn weaken market forces.

Then things get ugly

Although it can be advantageous to individual carriers, having weakened market forces is not good for the carrier collective, the driver collective, shippers, receivers, or consumers. It slows shipments and raises carriers’ cost and their complexity of doing business, and it increases the frustration level of drivers everywhere.

“Weakened market forces” doesn’t sound very ominous, but they are responsible for virtually everything “bad” on the driver side of trucking – the driver shortage, truck parking, high turnover, attrition, special people who won’t let drivers use bathrooms, absenteeism, skyrocketing driver costs, questionable lease purchase schemes, fuzzy use-a-payroll-agency-as-a-meat-shield business models, predatory towing, power imbalances, ELDs, and even laws like AB5. All of these are downstream symptoms/aftereffects of weakened market forces, which is the true problem/issue.

At a high level, the labor market is seeking the missing data so it can return to a state of equilibrium. It’s not getting what it wants, so it’s using a driver shortage to get everyone’s attention. It’s the economic equivalent of making a scene at a restaurant.

The shortage will continue to worsen, growing both in size and power until the trucking industry acquiesces and the driver market gets what it wants. That latter is very unlikely to happen since having weakened market forces is advantageous to individual carriers.

Related Poll – AB5 Butterfly Effect

As a result, the shortage will continue until the widespread adoption of autonomous trucks. As the non-existent electrification of our national highway system will stymie widespread adoption for decades to come, the pain that the shortage will inflict along the way will most likely be measured in trillions of dollars.

It’s super easy to prove in only 23 words

There is a large shortage of drivers, yet drivers are underutilized to the degree that their combined lost productivity can offset the shortage.

Those two things don’t generally coexist to any appreciable extent. If a shortage of supply and a big pile of supply were in the same room, so to speak, they’d offset. The lost supply from the underutilized drivers would offset the shortage. Well, normally it would, but it doesn’t in this case because “things” aren’t working quite right.

Macroeconomically speaking, the only way that these two conditions can coexist is if market forces have been weakened.

Implications

Virtually everyone is looking at the shortage all wrong. The shortage isn’t about drivers or even low pay. It’s about “bad” data.

Why our solution works

SlipSeat’s strategy is to give the labor market what it wants, thus eliminating the labor market’s need to wield the shortage. It’s the economic equivalent of eliminating John Connor by terminating his mom (but without the wild explosions and evil robots).

Our solution produces “good” data, which can retrain the economics of the labor market, restoring market forces along the way. Then, “things” will work a lot better and the big pile of supply will offset the shortage.

If we’re blessed with success, the pain that the shortage inflicts should only be measured in billions of dollars.

“Hasta la vista, baby”